There’s a lot of flawed thinking and anecdotes that underpin much arts fundraising ‘best practice’ today. That’s why the National Arts Fundraising School, with support from Ogilvy Consulting and ACE, set up the world’s largest field1 experiment in arts and culture fundraising. Over six months we tested a whole range of fundraising techniques to establish what really works and how well. We subsequently repeated the experiment in Australia and Estonia. And finally we ran a large scale experiment in Birmingham Museums which you can read about here. One of the techniques we tested was donation boxes: physical and electronic.

1. A field experiment means you test various approaches in real situations as part of a Randomised Control Trial.

Aren’t donation boxes a simple and easy way to fundraise? Don’t they give audiences/visitors a chance to make a gift to support your work? Well yes, they maybe can if properly placed, designed and nurtured- but as currently used they suffer from five problems:

- They don’t produce very much

- They confuse our brains

- They’re in the wrong place

- They’re badly designed and looked after

- They’re transactional not relational

Let’s look at each of these in turn:

1. They don’t produce very much

Frankly, it’s hard to tell how much cash donation boxes do produce. NONE of the ten arts agencies I approached informally in some initial research were willing to declare how much they gained from their box. But I know from other research that some boxes in smaller museums often produce as little as £20 a week. And contactless, often seen as the next big thing, doesn’t necessarily produce more2.

The data when it does exist is worrying. When the mighty Science Museum had donation boxes only 20% of the 4M visitors met the very modest suggested donation of £5, raising the grand total of £110K a year gross. From 4M visitors! When the Museum changed its approach to use decision science principles it stepped its income up to £1.4M a year. When Birmingham Museum Trust adopted the Decision Science approach, the donation box using the principles raised 25% more in donations with only 25% of the visitor footfall. Science works. Decision Science works impressively.

Below is an example of the previous very cool and artwork-y Tate Modern donation box. (They do try to make them pretty, but the new one isn’t any better.) It doesn’t look very full. According to their last annual report across Tate’s four sites they had 8.4M visitors last year. I’d be surprised if they got much more than £200K — x2 the Science Museum’s rate. If I’m right then that’s less than 2.5p a visitor. Maybe we need to re-define ‘popular’ if that’s the best level of giving that institution can secure. Just to be clear I’m not singling out Tate. This is, however, a criticism of major institutions with the footfall to drive large donation levels who produce really poor results.

BTW — I’m not opposed to boxes as such. Just the way they’re currently rolled out and used.

2. In one large North West gallery the contactless approach produced even less that the donation box- average of £28 a month versus £78 from static boxes.

2. They confuse our brains

Museums, galleries, theatres and venues tend to divide into two:

- Those who charge for admission

- Those who don’t

The problem here is if you make a big splash about being free and then ask people to donate, you may be asking people to switch from what Nobel Prize-winning decision scientist Daniel Kahneman calls System One – ‘wow, free! I like that, it makes me feel good’ to System Two – “hmmm this poster seems to be saying the museum can’t make the ‘free’ thing work. How much do I think I need to contribute?”

On the other hand, if you charge for entry and then ask for a donation the reverse is true: “So why are tickets £10 if you need to charge more to make the business model work?”

Let’s be clear: It is possible to ask for a donation after a ticket cost, but you need to engage an emotional response. For example, by asking for support towards a specific emotional element of your work.

For more on this see the detail in that Birmingham Museum Trust blog here.

3. They’re in the wrong place

So for those who do charge it’s a little weird for most visitors that just after they’ve paid to enter a venue, they are confronted by box seeking an additional donation often with the legend ‘we’re a registered charity’, as though those magical words would cast a Harry Potter style ‘donatiamus’ spell. There seems to be a theory that people would give more if they knew arts organisations were charities. Is that true? Is legal tax status really the barrier?

So, is the answer to add a fixed ‘voluntary’ donation, as the Tower of London and many theatres do? What the science tells us is that by fixing the sum it works as a default. People are inclined to go with a default. The downside is this seems to reduce the desire to make a gift-, and commoditise it to a small restricted System Two sum. So you may get some £5 add-ons to the ticket price, but you miss out on the chance for much greater gifts.

For those who don’t charge to enter where the donation box is places seems to be a pretty random matter. But interestingly if you think about it for minute, a box should be in one of two places: one is before you enter — so ‘please make a donation…before you’ve had the experience.” The other option is on exit, whether it’s a performance or an exhibition, and you’ve enjoyed the experience and should be feeling most positive. (In our experiment we’re testing both approaches.)

For the moment one good choice is to place mini-boxes beside specific sections. We worked with one famous museum and suggested they have boxes around the museum at key points with signage: “You could help to preserve this manuscript”, “you could fill this education room with children.” Income goes up at these touchpoints. We’re testing this more widely now.

4. They’re badly designed and placed

Aside from an almost universal use of Perspex, the most common design feature is simply a hole to put money in. My guess is the Perspex is meant to be a rudimentary piece of psychology to ‘normalise’ giving £5 or whatever is the ‘desired’ donation, so the clue we give visitors is to put lots of £5 notes in the box. This would probably be good move if it was well executed. Again, the science tells us that people like to do what others do. So if we see people putting money in a box, or see that many others have done it we will follow suit. However, what most boxes say visually (see below and Tate above) is the unpopularity of giving. Most boxes are empty.

Aside from an almost universal use of Perspex, the most common design feature is simply a hole to put money in. My guess is the Perspex is meant to be a rudimentary piece of psychology to ‘normalise’ giving £5 or whatever is the ‘desired’ donation, so the clue we give visitors is to put lots of £5 notes in the box. This would probably be good move if it was well executed. Again, the science tells us that people like to do what others do. So if we see people putting money in a box, or see that many others have done it we will follow suit. However, what most boxes say visually (see below and Tate above) is the unpopularity of giving. Most boxes are empty.

You need to make the box prominent too. Notice the box under this section title on ticket desk is also kind of stuck between other bits of ‘stuff.’

You can make a box look better as in the example below from the Horniman Museum showing before and after.

Tap to donate offers slightly different opportunities, but here notice that the gift has defaulted to a mere £1. So this electronic box easier to use, but it’s still not asking for a lot of money… in fact less than a cup of coffee in the café. Maybe we don’t believe enough in our cause.

5. They’re transactional not relational

My final complaint is the biggest one. Collection boxes go back to a very old school view that the donor is just that — a source of money and nothing else. You make a donation, but I don’t really care who you are or why you gave. I mostly can’t even be bothered to give you a personal ‘thank you.’ Such a donation box means that the visitor or event attendee is simply a provider of cash that you need and want. The box is a way to get that cash. And when they have given money the transaction is over. That’s not a relationship.

Some agencies do try to make the donation tax efficient through gift aid. So there is a need to collect more info, and with that comes an opportunity to communicate more. But sadly even collecting this information for a gift aid is deeply transactional.

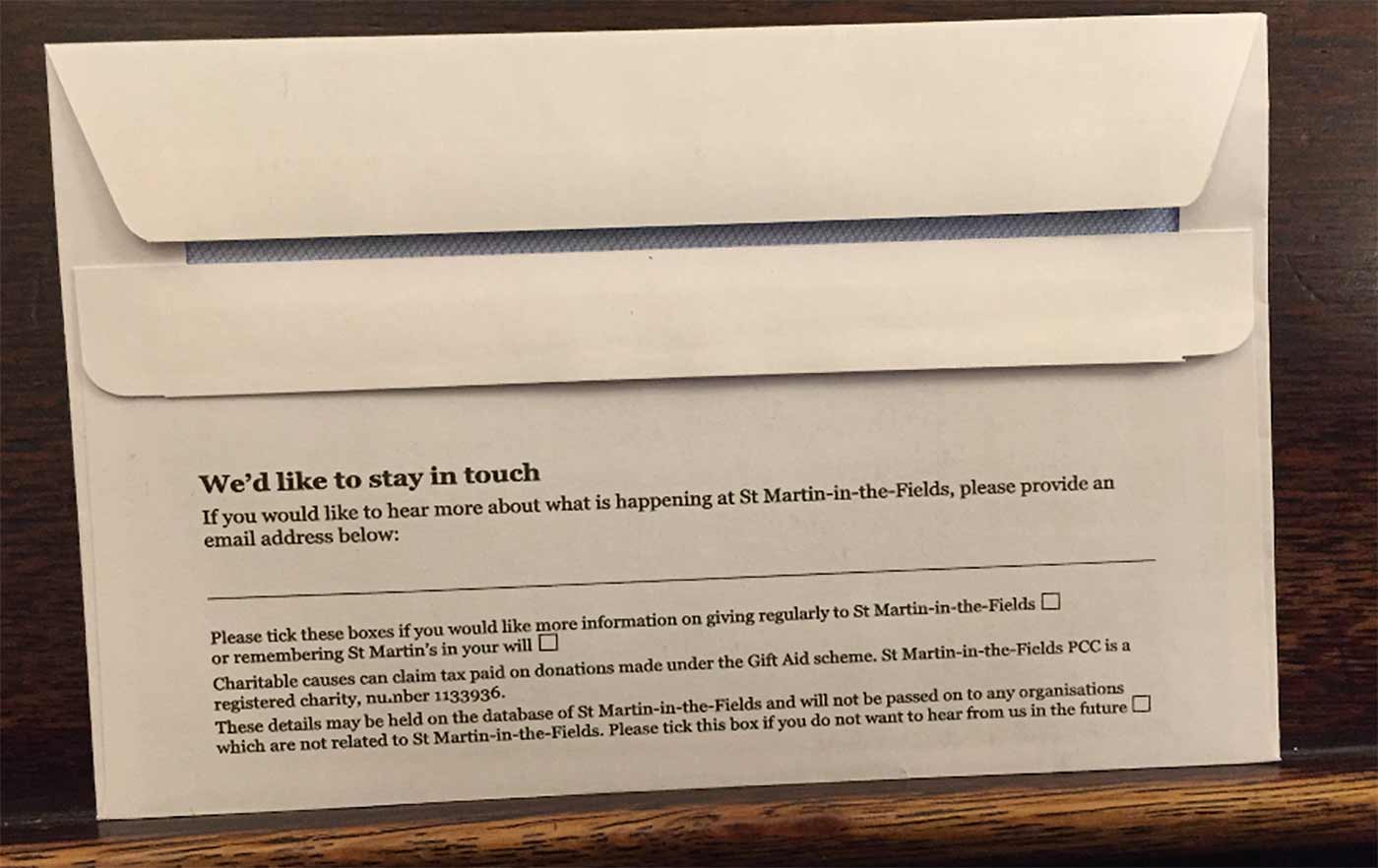

I love St Martin’s in the Fields in London. Both their fantastic classical music series and their terrific social work. But when they ask me for money to put in a box there’s nothing about what they do with the money, or how I’m helping — or even how grateful they are — it’s all about the tax. I filled in my last envelope having been moved by Handel’s Messiah. It was a great time to tap into my positive feelings, but below is what I was confronted with.

This kind of writing is so antipathetic to everything we say we’re trying to do about relationship. If you think about that person filling in the envelope or putting money on the box as a potential long-term supporter, then you want to get to know them and to nurture their giving.

Put simply, given a choice of someone’s email address or a £5.00 donation…I’d take the email every time. Because I’m sure over time I could encourage people to give more AND engage them in other ways.

Bernard Ross runs the National Arts Fundraising School www.nationalartsfundraisingschool.com, and is director of =mc consulting, a management consultancy working worldwide for ethical organisations.

Bernard Ross runs the National Arts Fundraising School www.nationalartsfundraisingschool.com, and is director of =mc consulting, a management consultancy working worldwide for ethical organisations.

He has written eight award winning books on fundraising and social change. His most recent, with Omar Mahmoud, formerly Head of Global Knowledge at UNICEF International, is Change for Good- behavioural economics for a better world. It explores how decision science is changing the world of fundraising and campaigning. He led the world’s largest filed experiment on arts fundraising with 11 UK arts and cultural agencies. You can find out the results of that experiment here.

He has advised many of the world’s leading INGOs on strategy including UNICEF, UNHCR, IFRC, ICRC and MSF. Recently he’s raised money to refurbish France’s most famous monument, for a museum to house the world’s largest dinosaur in Argentina, and to save the last 800 great apes in Africa.